The past few years catapulted retail into a digital transformation.

When shoppers were stuck indoors due to COVID-19 restrictions, retailers started investing more in digital strategies to grow sales and entice new buyers. While this meant expanding order pickup technology or creating a more user-friendly e-commerce site, it also meant a push toward augmented and virtual reality.

From trying on glasses and makeup using smartphones to creating more tech-enabled fitness equipment, brands continue to invest in the space.

This also means brands are finding new and varied ways of collecting and using consumer data — a fact shoppers are increasingly aware of.

Consumers want more transparency from companies about how personal data is used, according to Cisco’s consumer privacy survey of 2,600 adults across 12 countries, including the United States. The study found that privacy laws are mostly viewed favorably by consumers. That may be because respondents indicated they are very concerned about how personal information is used in artificial intelligence settings.

When asked what they think is the most important action a company can take regarding data transparency, 39% of respondents said providing “clear information on how my data is being used” is the top priority, per Cisco. Of the 43% of those surveyed who said they are not able to protect their data effectively, 79% said this was because they can’t figure out how companies are actually using it.

U.S. state governments aren’t waiting for companies to make that information clearer either.

In 2022 so far, two new state laws have already been signed regarding data privacy, according to the International Association of Privacy Professionals’ 2022 U.S. State Privacy Legislation Tracker, which was last updated on October 7. Three other state laws were signed between 2020 and 2021. Nine other state bills are active and nearly 50 are in inactive statuses across the country.

This indicates that state-level momentum for privacy bills is at an all-time high in the country, according to the IAPP. And tighter scrutiny comes just as companies like Walmart, Peloton and Snap are diving deeper into tech that has the potential to collect biometric identifiers.

It isn’t just new legislation that could impact how companies gather consumer information, as some existing laws are already changing the way brands use technology. One decade-old state law has put retailers in a unique spot, and has already taken multiple of them to court.

Welcome to Illinois

In 2008, a biometric privacy law was passed in Illinois that has recently thrown a wrench in brands’ plans.

The Biometric Information Privacy Act— commonly known as BIPA — defines biometric data or identifiers as “a retina or iris scan, fingerprint, voiceprint, or scan of hand or face geometry.” These characteristics are unique and specific to individuals, whereas more broad characteristics (such as having brown-colored eyes) can apply to many individuals.

The law was enacted nearly 15 years ago because “public welfare, security, and safety will be served by regulating the collection, use, safeguarding, handling, storage, retention, and destruction of biometric identifiers and information.” It also specified that while private information like social security numbers can be changed, biometric identifiers are tied to a person’s biology.

BIPA requires that private entities collecting biometric identifiers must inform people of its collection, the length of time such information is stored and receive a written release from a person to do so. It also states that entities cannot sell, trade or otherwise profit from the collected biometric information.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security defines biometric data more broadly as “unique physical characteristics, such as fingerprints, that can be used for automated recognition.”

BIPA outlines what it does not consider to be a biometric identifier as well, which includes information from written signatures to demographic data to donated organs.

What makes this law more unique (and more concerning for brands) compared to other state laws is the fact that citizens, not just the government, are allowed to sue under it, according to Matthew Kugler, professor of law at Northwestern’s Pritzker School of Law.

“The Illinois statute lets you file private lawsuits for guaranteed payouts,” which has driven litigation in the state, Kugler told Retail Dive.

Walmart, Best Buy, Kohl’s, Giorgio Armani, Louis Vuitton and Estee Lauder are all on the receiving end of lawsuits in Illinois under BIPA. Several of these cases are related to virtual-try on technology.

In 2021, Sephora, Meta and TikTok all settled cases in which they were sued for violating the law.

But why has a law from 2008 suddenly brought on so many lawsuits over the past few years?

“At the time this law was passed, no one was really paying all that much attention,” said Kugler. “And what seems to have been the case is a couple of people who were paying attention, like some aspects of the banking lobby, got exemptions under the law.”

That’s changed over the years though, as more companies are being brought to court. Now brands are paying attention, according to Kugler, and many have lawyers on the books who are well versed on the topic.

Treading lightly

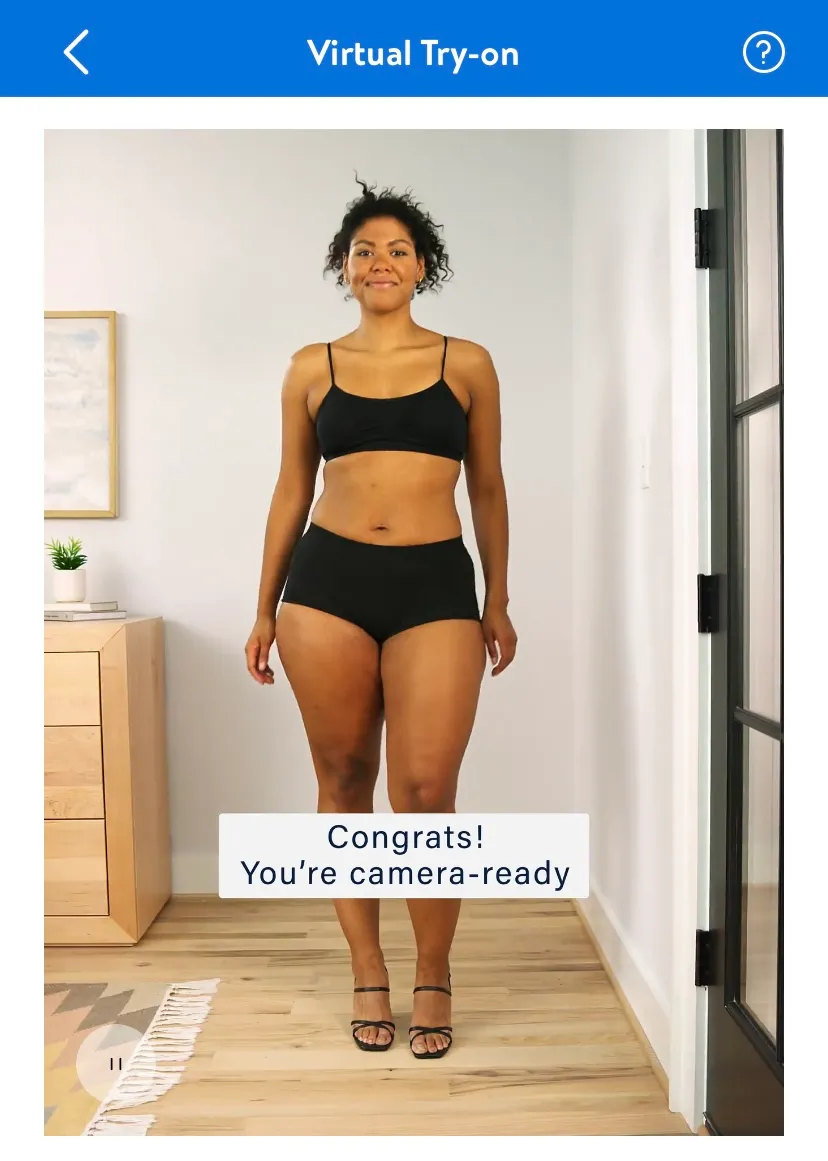

In September, Walmart released a large upgrade to its virtual try-on capabilities for apparel. With its new Be Your Own Model functionality, shoppers can try on over 270,000 women’s clothing products by uploading a full-length image of their body — which is saved to a user’s account — through the company app. The function specifically recommends users wear fitted, minimal clothing and heels.

When asked if any company employees were able to access those customer images, a Walmart spokesperson told Retail Dive “we are focused on protecting our customers’ personal information and do not make these images broadly available to our associates.”

Walmart’s new feature doesn’t copy and paste the image of a shirt or dress onto your photo, but it uses what Walmart calls “algorithms and intricate machine learning models” to realistically drape the clothing over the body.

The spokesperson also said that “some images may be used to improve object recognition using computer vision for this tool” after they are blurred and anonymized in an automated process.

When it comes to data used in machine-learning and AI, 54% of respondents in Cisco’s survey said they are willing to provide their anonymized data to improve the technology. However, 60% expressed concern over how their data is used for AI by companies.

The anonymization of data, generally speaking, doesn’t always protect everything about consumers’ identities, according to Jiaming Xu, associate professor at Duke University. Xu says that the unique behavior patterns of an individual can still be used to identify someone even after the data about them has been anonymized, according to a blog post from Duke University’s school of business.

When a consumer uses Walmart’s new function in the app, they must agree to a list of privacy terms, including the acknowledgment of the following:

“This tool uses body scanning technology to collect and process your image and biometric information to measure your unique body features.”

Another condition says the “experience may require your measurements and images to be shared with a third-party service provider.”

Other aspects of the privacy terms include a note about how long the images are stored for (no longer than four years) and what happens to them if a user’s account is deleted. This could be an indication that Walmart is aware of the unique storage and destruction aspects of BIPA.

The same Walmart spokesperson told Retail Dive that though the company does not currently share any customer images, “it is our plan for any customer images to be blurred and anonymized before sharing with a third party.”

When asked if the functionality collects biometric data, the spokesperson said “we only collect biometric data consistent with our Walmart Privacy Policy.” That privacy policy might not be read by all customers though, as only one-in-five Americans say they always or often read such policies, according to a Pew Research survey in 2019.

As retail tech advances, ‘get your paperwork in order first’

Regardless of whether or not a company is based in Illinois or is actively working with data that falls under BIPA, many are still cautious.

“Even companies that don't do business in Illinois are trying to be a little bit better with their disclosures to take into account these other laws that are emerging,” said Kugler.

At-home fitness brand Peloton has a detailed biometric and fitness data privacy policy as well, outlining information on the retention and destruction of such data.

The policy states the company “may process your Biometric and Fitness Data to make automated decisions about you.” It also mentions that “biometric data is temporarily processed by your Peloton Guide to support the functionality of the product.”

However, when asked to confirm if the Peloton Guide — a strength training device with a camera that uses AI —collects biometric data, a company spokesperson told Retail Dive that it does not. If it does begin to collect such data in the future, Peloton will have members “go through a consent flow prior to any collection being gathered.”

In general, retailers using technology involving cameras may want to be up to speed on privacy laws, according to Kugler.

“If your product involves a camera it isn't that difficult to tell apart, for example, members of an individual family based on their faces. And that is facial recognition,” Kugler said. “So if you're thinking of doing something like that, certainly you want to get your paperwork in order first.”

Social media platform Snapchat — which is run by parent company Snap — has learned this the hard way.

Snapchat has steadily been increasing its usage of augmented reality lenses for retail applications. In October, the platform announced a collaboration with Disguise to release Halloween costume virtual try-on lenses.

It’s the platform’s lenses and filters that landed it in a class action lawsuit under BIPA. The company settled the suit in August for $35 million.

“You want to know whether it's OK to have a virtual try-on room when Walmart does? Give them a year. Find out. In the privacy space, companies like Facebook will always be sued first.”

Matthew Kugler

Professor of Law at the Northwestern Pritzker School of Law

When asked if Snapchat’s latest Halloween costume lenses collect biometric data, the company told Retail Dive that they do not collect biometric data tied to specific people, but instead identify eyes or noses from a face generally. The company denies violating BIPA, but earlier this year added an in-app consent notice for Illinois users.

BIPA may have set the stage for such litigation, but it isn’t the only state where brands are being sued for privacy violations.

Sephora agreed to settle a California lawsuit in August for $1.2 million after the state claimed it was selling customer data without informing them. The lawsuit came from the enforcement of the state’s California Consumer Privacy Act, which started taking effect in 2020.

Additionally, Texas opened a lawsuit against Google in October, claiming it violated a state law requiring companies to inform citizens of the collection of biometric identifiers.

With more states enacting stricter privacy policies to protect consumers, some retailers may be wary to advance their technological capabilities. That skepticism might be useful, according to Kugler.

“There's often a kind of vendor-driven acquisition of new technologies, or someone sells you on this latest and greatest thing, and a fair amount of skepticism is warranted,” said Kugler. “In those cases, if your business is doing just fine without it, ask yourself: 'Do you really need this?'”

Whether it comes to dealing with Illinois or California state laws, Kugler’s advice for retailers is simple.

“There’s always a great virtue for not being the first to do something,” said Kugler. “You want to know whether it's OK to have a virtual try-on room when Walmart does? Give them a year. Find out. In the privacy space, companies like Facebook will always be sued first.”