NEW YORK — Privacy laws should be as much of a concern to grocers as ad partnerships as retailers expand their in-store and online retail media efforts, an Albertsons official said at a recent industry event.

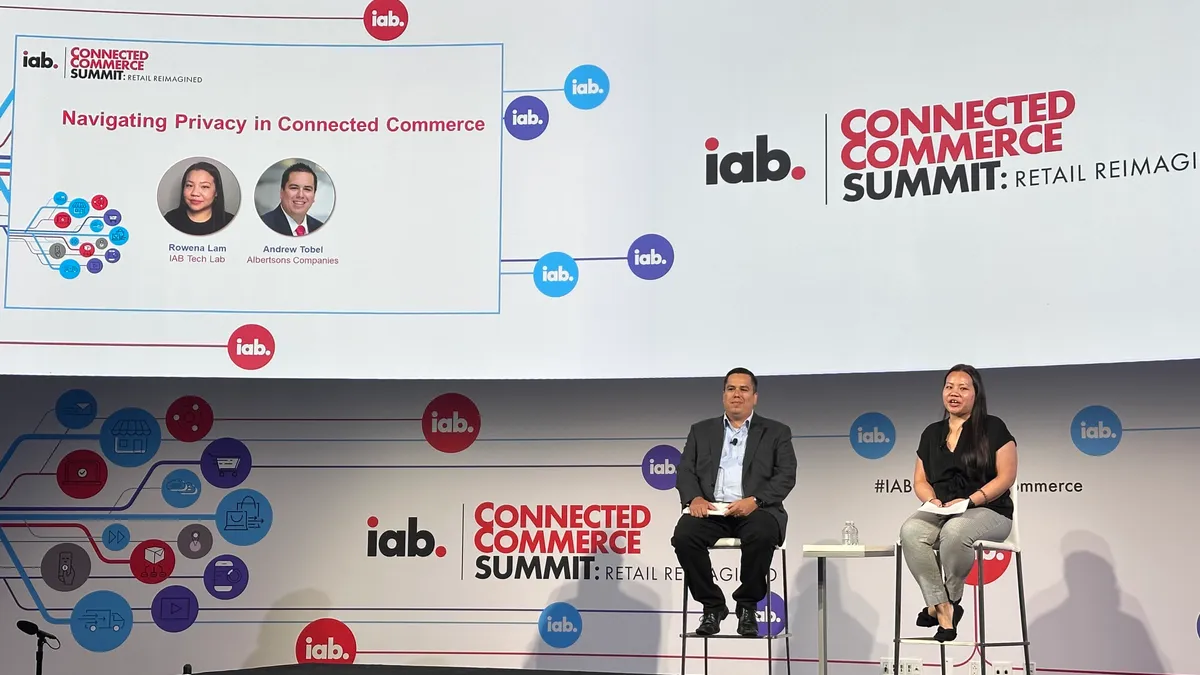

The industry has been moving away from collecting personally identifiable information (PII) like first and last names, email addresses and phone numbers and toward personal data, which is broader than PII and incorporates “pseudonymized identifiers” like a mobile ID, platform ID or a cookie ID, Privacy Counsel for Albertsons Andrew Tobel said during a panel at the Interactive Advertising Bureau’s Connected Commerce Summit.

As a result, privacy law has pivoted to regulating the personal data retailers do collect, Tobel said on Sept. 18 during the session, which focused on how retailers can best navigate privacy laws and understand where they currently stand.

These days, privacy laws are more focused on the parameters of personal data, Tobel said.

“Even if the law doesn’t treat a specific data attribute as sensitive, you need to consider what your consumer expects,” he said.

Privacy laws today require retailers to have explicit terms around personal data and pseudonymized identifiers in their contracts with service providers, processors or third party companies outlining what those entities can do, Tobel said.

“Personal data” is an expansive term that also includes “sensitive personal data,” which can include people’s location, ethnicity and nationality — information that is vital to retailers and CPGs as an “effective driver” for ad campaigns and ensuring that ads reach the right audiences, according to Tobel.

Tobel broke down the origin of personal data into three concepts — direct, supplied and derived.

Direct data is personal information gathered right from the consumer and, according to Tobel, is the most impactful when it comes to creating creative and inspirational ways to engage customers.

Supplied data, on the other hand, refers to data that is purchased as part of identity graphing or audience segmentation capabilities, Tobel said, and, under privacy laws, falls into the category or “purpose specification.” Retailers purchase this kind of data for a specific purpose, and it can be used to create relevant ads or push notifications to consumers. However, this area can be a slippery slope as consumers may not be aware their data would be used in a different way than how they supplied it, Tobel said.

Meanwhile, derived data refers to inferences or predictions retailers and CPG partners make about customer behavior, whether an individual shopper or a group, Tobel said. Like supplied data, the rules that apply to derived data are subject to change under privacy laws’ consent requirements, and this needs to be taken into account when retailers work with their data science teams and partner with vendors.

Data clean rooms — secure and controlled spaces where multiple companies can compile data for joint analysis — can be an effective way to move forward with personalization-focused retail media efforts, as they are a “great privacy-conscious way to work with … consumers’ data,” Tobel said. However, one misconception about these data clean rooms Tobel pointed out was they are not “privacy safe” or a “silver bullet” that can work around privacy laws.

The law requires data to be available to ad and CPG partners, according to Tobel. Retailers also must make available tools used within data clean rooms to process personal data collected by retailers, Tobel said.